A brief history of right-wing coalitions governing British Columbia

One who can unite the right has the clearest path to the Premier's chair

There will not be some kind of United Conservative Coalition Party on the BC ballot this election. Depending on who you ask, either United or the Conservatives walked away from the table, and curse words may or may not have been uttered. Social media was a communications race to see who could frame the narrative the fastest.

United sent details of their offer to the province’s media, which included running an even number of candidates, a non-aggression pact, and a “draft format” for dividing up the province's ridings for who can run for which seats. Also, all of United's incumbents would be safe.

That's a bold offer for a party that appears to be tied for third place in opinion polls. It would require dozens of nominated BC Conservative candidates to step down to benefit a party that kicked their leader out only a short time ago.

Depending on which polling company you ask, the BC Conservatives have been sitting somewhere around 34% (Abacus), 36% (Mainstreet), or 32% (ResearchCo) popular support. United sits at 13%, 14%, or 12%. The latter poll which has the Conservatives at their lowest is the one they cite in their press release that has United tied with the Green Party.

But even while laughing United off, the Conservatives must know that the stakes are high, as the likeliest path to government for either party involves neutralizing the other. When right-wing voters can coalesce under a single banner it usually goes well at at election time. For most BC’s political history — around 70% of the time since 1903 — a right-leaning party has been in government.

The first time BC elections were under a party system was in 1903, and for the first few decades it was like almost all Canadian provinces at the time: Liberal versus Conservative. That was until 1933, when the Co-operative Commonwealth Federation formed opposition amid the Conservative Party imploding after being in government for a few years.

In the 1941 election the CCF won slightly more votes overall than the Liberals, who lost 10 of their seats in the legislature. The Conservatives won enough to result in a minority government. After that election the two parties agreed to a formal coalition, and it worked for a few cycles, but eventually the two parties fractured and ran against each other again. This time, to ensure they would not split each other’s vote, the government introduced an alternative ballot system (ranking candidates 1, 2, 3 and so on). Then they could run for the same seats without the CCF sneaking up the middle.

Instead, voters used this system to send the new centre-right Social Credit League — a party that did not even have a formal leader at the time — enough seats to form their own minority government. Once the caucus chose W.A.C. Bennett as Premier, he called another election and governed for 20 years uninterrupted as the right-wing alternative to the CCF — which would change its name to the New Democratic Party in the 60’s. He also switched voting systems back to first-past-the-post.

Since then, more or less, the primary strategy on the centre-right has been to maintain a united coalition that can defeat the NDP. For 39 years it was the SoCreds. Occasionally the Liberals or Conservatives would take a seat, and in the 1972 election that brought the NDP’s Dave Barrett to power, they both did. Three years later Social Credit was returned to government with the NDP dropping barely a percent of their vote share, but the Liberals and Conservatives both dropping 9 points.

Nothing lasts forever, and when the Social Credit name became mired in scandal under Bill Vander Zalm, the return of the NDP to government allowed for a realignment. The Liberals had jumped from 7% to 33%, overtaking the SoCreds, and then being taken over itself by Gordon Campbell after its leader Gordon Wilson was forced out in scandal. Wilson formed a third party which succeeded only in re-electing himself.

Support for the Liberals grew under Campbell, whose “unite the right” credentials came from being Mayor of Vancouver with the right-wing Non-Partisan Association. The new “free enterprise coalition” Liberals won the popular vote in 1996 and swept all but two New Democrats from office in 2001. Campbell kept the coalition together until he resigned in 2010.

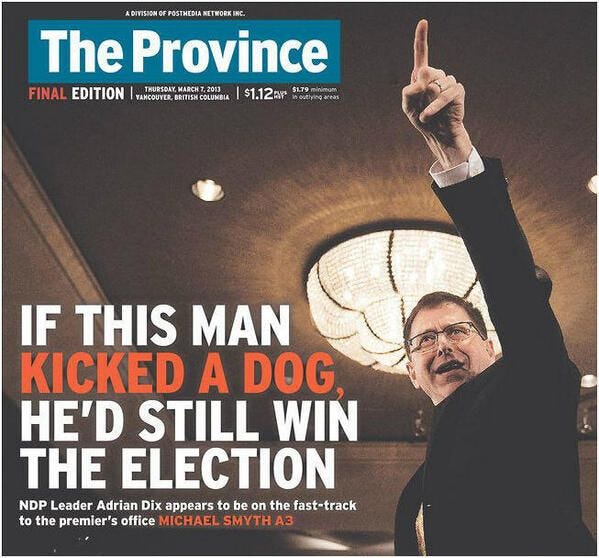

During Christy Clark’s premiership, the BC Conservatives started to grow in polling support under the leadership of former Conservative MP John Cummins. That support grew when one of Clark's MLAs, John van Dongen, crossed the floor and joined them. With the NDP polling high and the two parties at each other’s throats, it appeared all but certain that Adrian Dix would become the next Premier.

Van Dongen ultimately quit the Conservatives before the election and ran as an independent. Their polling lead evaporated, particularly after a poor debate performance by Cummins, and the BC Liberals began to recover. The NDP ran a lacklustre, overly cautious campaign that faltered badly when Dix flipped his position on the Kinder Morgan Pipeline. On election night Premier Clark was re-elected with a net gain of four seats. She began her victory speech with a jovial, “well, that was easy.”

While Clark faced a leaderless Conservative Party in 2017, growing concern among voters — her base included — regarding the influence of big money and environmental anxiety amid growing wildfires allowed the Green Party to appeal to disenfranchised voters and elect three MLAs. The NDP gained six seats despite their total vote share only going up half a percent. When the dust settled, the combination of NDP and Greens outnumbered Clark’s Liberals by a single seat. Clark attempted to continue as Premier with a minority government, but was quickly defeated in a confidence vote.

Once again the NDP are in government. The right-wing wants to defeat them, but is fractured between two parties. United has a team of experienced incumbents, organizers and deep pockets. Conservatives have the popular support and momentum.

They tried the first route: make a formal agreement in advance of the election like in 1945: don’t run against each other, govern as a coalition, and work out their differences after they’ve sent the NDP to the opposition benches. That road appears to be fully closed now.

Now both leaders have committed to running full provincial slates. There appears no chance of them working together, and the election only 146 days away. They will have to go route number two: unite centre-right and right-wing voters (and donors) under their banner — and obliterate the other party.