Matters of confidence

Minority parliaments have been some of British Columbia's most consequential

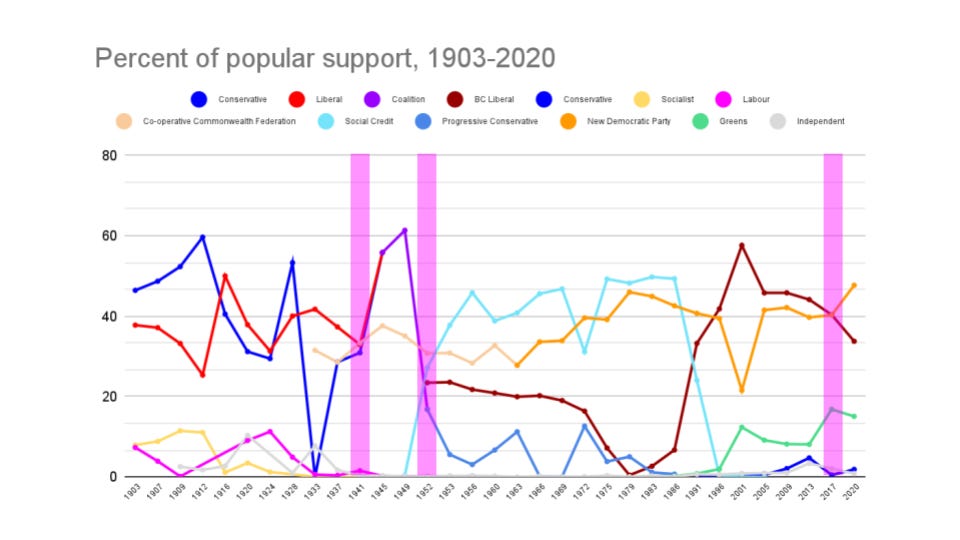

British Columbia has only had three minority parliaments before — from 1941-1945, during which provincial Liberals and Conservatives governed as a formal coalition; 1952-1953, where Social Credit governed briefly with the support of the sole Labour MLA; and 2017-2020, when the NDP and Greens signed a Confidence and Supply Agreement.

These three minority governments all signaled significant changes in BC’s political landscape. Duff Pattullo’s loss of his majority amid a rise in support for the Co-operative Commonwealth Federation led the Liberals and Conservatives to form a coalition government, with Pattullo being removed as leader by his party caucus for refusing to agree. That minority coalition reshaped the entire narrative in the province, with the former political rivals running a united slate of candidates to “stop the socialists”, which is still a common narrative for the right-wing today.

This approach has thus far been the most enduring, with the two parties running a joint slate of candidates, winning the next two elections and governing for 11 years.

The coalition that began with a minority ended with one as well. The Liberals and Conservatives ran separately in 1952. In the hopes of avoiding the CCF benefitting from vote splitting they implemented preferential ballots, assuming Liberals voters would choose Conservatives second and vice versa. They did not. Instead they chose the leaderless Social Credit Party, which elected one seat more than the CCF. The incumbent Premier, Boss Johnson, lost his own seat, as did Conservative leader Herbert Anscombe.

Technically, after any election the incumbent Premier can test the confidence of the house. If another party wins a majority, the Premier resigns. If a Premier has the support of enough seats, passing a piece of legislation designated a confidence vote demonstrates that they have the support of a majority of the elected representatives, which allows the government to continue to govern. The arbiter of whether or not a Premier has the support of the Legislative Assembly is the Lieutenant Governor.

John Hart, as leader of the coalition of Liberals and Conservatives, was easily able to demonstrate the confidence of the house. Boss Johnson, with no seat in the legislature, could not. The party with the most seats is then offered a chance to test confidence. In 1952, Social Credit had 19 seats, short of the 25 needed for a majority but still the largest party. The CCF had 18.

In order to pass a confidence vote, the legislature needs to sit and pass legislation. In order for the legislature to sit, it needs to nominate a Speaker. The Speaker's job is to facilitate the business of the legislature, and they are supposed to remain neutral in all proceedings. This essentially removes them from their party’s vote count, since they are only supposed to vote in the event of a tie. But in an evenly divided legislature, that could become a common occurrence.

The Social Credit Party, which had chosen former Conservative MLA W.A.C. Bennett as their leader, had only one seat more than the CCF, so nominating a Speaker from their party meant the CCF could argue they had an equal number of seats, and should be given a chance to test the confidence of the house themselves. In order to secure their minority, Bennett convinced sole Labour MLA Tom Uphill to vote with them, allowing them to nominate a speaker and still have the largest block of seats.

Once Bennett settled into his role as Premier, he engineered his own loss of a confidence vote. When this happens, the Lieutenant Governor has two choices — they can dissolve the legislature and call an election, or they can invite another MLA to form a government. In 1953, despite Uphill switching his support to the CCF’s Harold Lynch to make the argument they should be given a chance to test the confidence of the house, the Lieutenant Governor called an election. It resulted in a Social Credit majority.

Despite the minority of 1952 only lasting a year, it solidified a completely new organization — Social Credit — as the governing party for most of the next four decades.

The third time British Columbia had a minority ended only four years ago. In 2017 the BC Liberals won the most seats, but missed the mark for a bare majority by one. They were elected in 43 seats, the NDP in 41, and the Greens in 3. A majority at the time was 44.

Incumbent Premier Christy Clark and NDP leader John Horgan both entered into negotiations with the Green Party to try to get them to support their party in a confidence vote, so they could go to the Lieutenant Governor and show they had enough support to form a government. The Greens sided with John Horgan and the NDP. They signed a formal Confidence and Supply Agreement, with the Greens promising to vote with the government on the budget and confidence votes.

As the incumbent Premier, Christy Clark had the right to test the confidence of the house first. She formed a cabinet, and recalled the Legislature. Steve Thompson was nominated as Speaker, and cabinet ministers began introducing legislation. When they finally could run out the clock no longer, the NDP, supported by the Greens, amended the bill in front of them to read, “this government does not have the confidence of this House”. Clark then made the long trip to the Lieutenant Governor’s house.

Clark made one last pitch. She tried to convince Lieutenant Governor Judith Guichon that no party had the confidence of the house, and to dissolve the legislature and call an new election. Unlike 1953, the Lieutenant Governor declined, and invited John Horgan to form a government.

Horgan faced the same problem Bennett faced in 1952 — putting forward a Speaker meant an even tie in the legislature. The legislature could function but actually passing anything would likely become a constant conflict, with the Speaker being forced to vote regularly.

In the end, Liberal MLA Darryl Plecas stepped forward to be Speaker, leaving his party and sitting as an independent. From that point on, Horgan’s minority ran smoothly, until he himself requested that the Lieutenant Governor dissolve the legislature in 2020.

Like in 1952, where the minority was the beginning of a significant realignment, 2017 triggered the eventual implosion of the BC Liberals, who had governed for 16 years. Defeated in their last attempts to hold on, the party never really found its footing, and folded before the 2024 election.

The 2017 election also put the Green Party in the spotlight, as they are again in 2024. Premier David Eby, as the incumbent, does not need a formal agreement to recall the legislature. He has the right to test the confidence of the house, and unless the two rookie Greens are keen to hit the campaign trail again, they are likely to support the NDP in a confidence vote. However, if Eby wants to actually pass legislation, he'll need either the Greens, or at least two Conservatives, to vote with his party.

There are a few options. Eby could unite with the Green MLAs in a formal coalition, as John Hart and Royal Maitland had in 1941. He could simply start governing, being the leader of the party with the most seats, as W.A.C. Bennett had, and Christy Clark attempted. He could come to an agreement with the Greens like in 2017, and govern as a minority.

Or, if all that fails, and he tests the confidence of the house and doesn't have it, British Columbian voters will be given another chance to cast their ballots and try to elect representatives that can make it work.

> This is all assuming none of these seats flip in a recount the same day this post is scheduled to go out

Awkward.

Still a great piece.

Tom Uphill is a fascinating figure. Longtime leftist and only Labour MLA for quite a while. Refused to join or support the CCF for what are largely the usual reasons leftists hate one another. Ultimately delivered BC it's longest serving premier (but arguably only the second greatest according to the PolitiCoast bracket).