When I was a teenager, I was a voracious reader of fiction. Perhaps it had to do with being a queer kid in a small town, but I enjoyed spending more time in fantasy worlds than the real one. I would read every night, often well into the early morning, which would lead to falling asleep in class. I frequently had more than one book on the go at a time.

I still recall fondly R.A. Salvatore’s tales of Drizzt Do’Urden and his astral black panther, Guenhwyvar. I read every one of K.A. Applegate’s Animorphs series that I could find in the local library. And of course, rounding out the list of authors who use two initials instead of their first name, I read every single Harry Potter book. I even lined up at midnight for the release of The Order of the Phoenix.

In hindsight, it was no surprise that the story of a kid escaping a closet under the stairs for a magical fantasy world resonated with me. It was exactly the kind of escapism I was looking for as a teenager.

For years after the final book, The Deathly Hallows, I did not think much about the series, but it lived on my bookshelf for many years. I also did not think much about the author until she suddenly decided to insert herself into BC politics.

Card’s game

While I was a student at the University of Victoria, the movie adaptation of Orson Scott Card’s Ender’s Game came out. While I was a little too young for the novel to have been a formative part of my childhood reading — it came out in 1985 — for folks a little older than me it was their equivalent of the Harry Potter series. It followed the same bildungsroman formula as the Potter books, with a child being whisked away to a school — this time in space — where they are pulled into a conflict bigger than themselves that defines their transition into adulthood.

Having never read the novels, I knew nothing about the series or its creator. However, prior to the film’s release queer organizations organized a boycott led by Geeks OUT in New York. The reason was not the film itself, but the author. Orson Scott Card has a long history of opposing rights for gay people. He openly supported laws criminalizing homosexuality, claimed that most queer people are “self-loathing victims of child abuse”, and actively campaigned to ban same-sex marriages.

“Laws against homosexual behavior should remain on the books, not to be indiscriminately enforced against anyone who happens to be caught violating them, but to be used when necessary to send a clear message that those who flagrantly violate society's regulation of sexual behavior cannot be permitted to remain as acceptable, equal citizens within that society.”

Orson Scott Card, Sunstone Magazine, 1990

Card, as an executive producer on the film, stood to make a significant amount of money off its success. As a board director for the National Organization for Marriage, which fights against same-sex marriage and adoptions, it was likely money Card made off the movie would be used to fund advocacy efforts against queer people. The more successful the film, the more he could give to his cause. If it was successful enough to launch media franchise — as the studio hoped — he would be all the richer.

The film did well at first — it was top of the box office on its opening weekend — but the reviews were not favourable. It was not Card’s anti-gay views that sunk the film, but poor pacing and over-reliance on CGI. Despite a strong first weekend, it ended up being one of the biggest box office bombs of 2013, losing the studio tens of millions of dollars.

Still, I am a big fan of science fiction and wanted to see the film, so I torrented it and watched it illegally. I thought it was pretty good, especially the rivalry between Asa Butterfield and Moisés Arias’ characters.

Fictional revisionism

Creators of major media products have a habit of trying to change details after they are out. George Lucas kept adding CGI changes to the Star Wars films decades after their original release. There are seven different versions of Ridley Scott’s Blade Runner. One of the artists most guilty of arbitrary revisions is J.K. Rowling.

Well after the final book was published, the server on the Hogwarts Express — the magic train that takes the children to school — became an immortal being who spent her life making sure that no children escaped. Rowling decided Professor McGonagall was once engaged to a regular, non-magic person, and also that wizards pooped on themselves. But the one that raised my eyebrow the highest was Rowling declaring that Albus Dumbledore, the headmaster of the fictional school attended by Potter and his friends, was totally gay the whole time even though this was never mentioned or alluded to anywhere in the books.

Even as a fan, the reveal seemed hollow to me. If you’re not going to actually include a major character point like that in the book itself, then why bother? If I wanted to reimagine the characters as queer, there is a mind-blowing amount of fanfiction I could read.

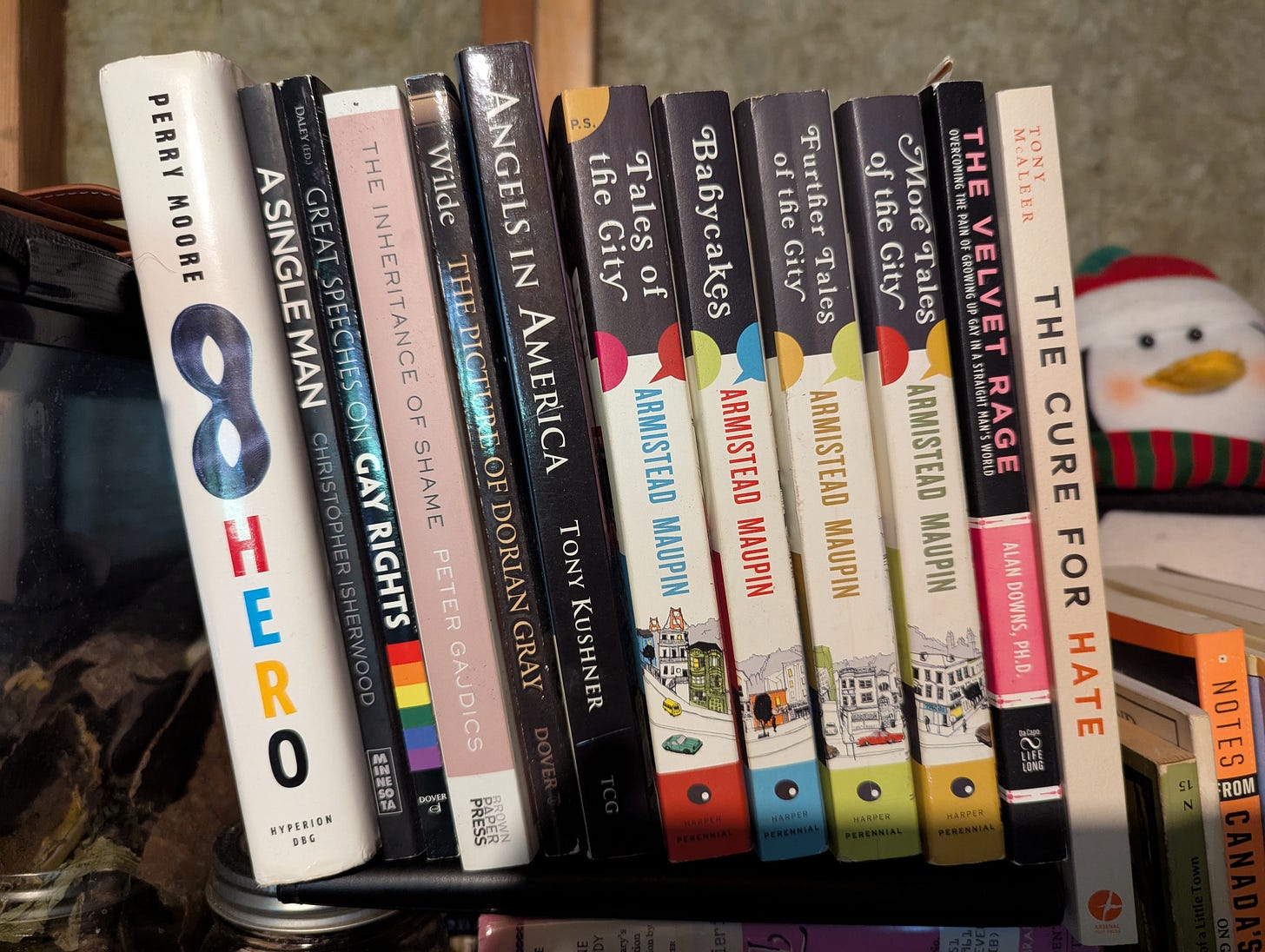

It’s not like queer characters couldn’t be in books. The same year Rowling recast Dumbledore as gay, Lev Grossman released The Magicians, a fantastic series with several queer characters, including one of the main protagonists. Two years prior, Perry Moore’s Hero had come out, whose lead protagonist is gay. Declaring a character retroactively queer was not groundbreaking in 2009.

By that point I was not as engaged with the Harry Potter franchise. The movie version of The Half-Blood Prince had just come out and it was… fine. I thought the later books lacked the depth and excitement of the earlier ones, and seemed to just jolt from one conflict to another. The movies felt the same. Plus I was annoyed they had split up The Deathly Hallows into two films even though, page-wise, it was the same length as the previous book and shorter than The Order of the Phoenix.

The monster that lurks below

In 2020, J.K. Rowling announced her new children’s book, The Ickabog. By that point, Rowling was no longer a struggling writer trying to single-parent, but one of the wealthiest authors in history. She presides over a multi-billion dollar media franchise and lives in a sprawling mansion in Scotland. From her place of comfort and wealth, she spends most of her time online.

Rowling uses social media to do more than rewrite parts of her book series, she also shares her thoughts on political issues. In particular, she began to target transgender people. She liked posts mocking trans people, followed anti-trans activists, and criticized trans people who tried to explain what it’s like to live as a trans person in today’s political climate.

When Rowling posted online that she was releasing a children’s book, friend of mine and political activist Nicola Spurling expressed concern online with Rowling being a role model for children. Spurling, a trans woman who was outed by the Green Party in 2017, has been a long-time activist for the queer community and a recognizable figure in BC politics. However, it was still surprising when the massively wealthy and supposedly busy author responded directly.

“Unless you want to hear from lawyers, you might want to rethink that tweet. I’m not wasting my time arguing with wilful misrepresentations of my views on transgenderism – your timelines show you’re not big on truth – but making serious insinuations like this comes with consequences.”

J.K. Rowling, May 26, 2020

If Rowling felt her views were being misunderstood, she did not help her case when a few days later she began posting confusing and contradicting thoughts on trans people. At first she posted, “I respect every trans person’s right to live any way that feels authentic and comfortable to them. I’d march with you if you were discriminated against on the basis of being trans.” The next day, she mocked a headline that said “people who menstruate” — referring to the fact that some intersex and trans people also experience menstruation. To try to clear the air and quell the controversy, she posted a long blog post outlining her views on sex, gender and sexuality. It did not work.

The post is noteworthy for two reasons. One, it is far more nuanced and thoughtful than the overt cruelty Rowling employs nowadays. Today, Rowling makes no secret of her hatred and animosity towards trans people. Just last year, she falsely accused an Olympic athlete — from a country where being transgender is illegal — of being a man pretending to be a woman to gain a competitive advantage. Her posts became so vitriolic people began to theorize she was being affected by black mold. She financially backed a legal challenge against recognition for trans people.

This is where she shares an important commonality with Orson Scott Card — she uses her vast wealth from the Harry Potter franchise to fund anti-queer causes. She is not just an opinionated author; she is an important financial contributor to anti-trans infrastructure. Which also means the millions she receives from the ongoing success of the different Harry Potter media will likely be used to hurt, oppress and delegitimize human beings.

The other way her post is noteworthy is that her claims of backlash and “cancellation” are based entirely on people online reacting to her posts. This was only five years ago, and it was already clear that Twitter amplified the worst of people, manufacturing outrage to drive views, and was overwhelmed with bots and fake accounts creating controversies. It’s their whole business model.

The medium is the message

Most of J.K. Rowling’s controversies over the last five years stem from her writing on social media. Rowling posts something, the algorithm solicits rage from other users, Rowling declares herself the victim, and the cycle of anger continues. Social media is, for the most part, a form of entertainment, and Rowling's descent into bigotry has created an entire industry of think pieces and rage-bait.

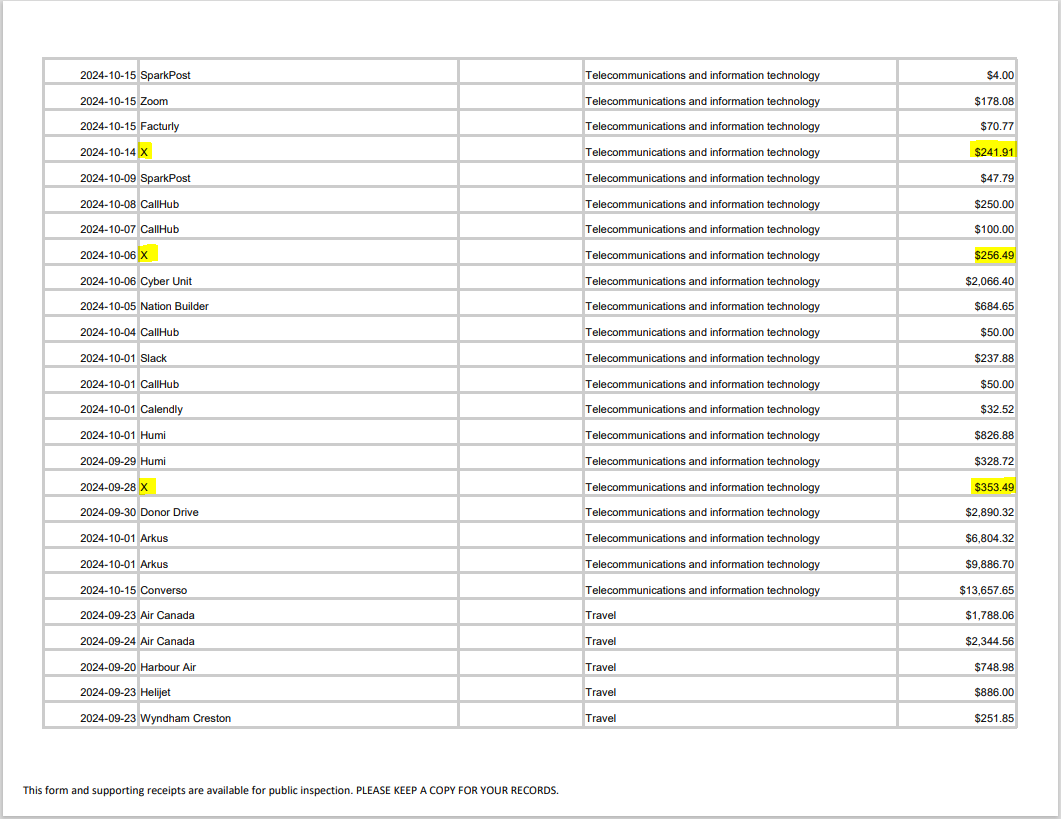

The platform Rowling uses is Elon Musk’s X — formerly known as Twitter — which revolves entirely around using rage-baiting to drive engagement. If people are angrily checking their feeds to find out what is going on, they're generating views that X turns into advertising dollars. Much like Rowling suddenly declaring that wizards defecated on themselves, Musk cannot stop tweaking his work.

Never has this been more apparent than the sudden extremist outbursts of Musk’s favourite child, Grok. The large-language model chatbot spent last week falsely accusing a user of celebrating the deaths of children, declaring Jewish people the perpetrators of anti-white sentiment “every damn time”, praising Adolf Hitler, and calling for a second Holocaust.

Grok’s style of engagement is a reflection of Musk’s design. Much of the philosophy that came out of his chatbot has been fomented by Musk himself, using his media platform to amplify misinformation and far-right views. Grok gets its data from the collective contributions of the people and bots that post to X. It became a self-declared Nazi because its dataset is full of Nazis.

Instead of a novel, Musk has written a program — or at least takes credit for writing it — that is telling the story of the platform it was unleashed on. As long as people are tuning in to catch up on the latest chapter, the cycle continues.

That has not stopped BC politicians from using — and funding — Musk’s media platform. The Vancouver Clerk's Office exclusively posts updates to X, and it is the only platform where you can follow all ten city councillors. The province has a $5 million contract with Musk’s Starlink.

By buying in to these media platforms, people inadvertently end up being the source of funding for abhorrent, dehumanizing causes. Orson Scott Card successfully funded efforts to repeal same-sex marriage in California. Rowling used her wealth to strike down protections for trans people. Musk uses the money political parties and other advertisers funnel to his platform to develop his violent, bigoted chatbot and influence US elections.

It’s becomes impossible for me to separate the creation from the creator. I loved Harry Potter as a teenager, and I enjoyed Ender’s Game when I watched it. I used to enjoy Twitter as well. But at a certain point I cannot think about them without thinking about how much pain the owners of those creations cause with the profits from our entertainment.

I was so disappointed when I learned what a horrible person Orson Scott Card is. I’d read Ender’s Game years before and thought it was a masterpiece. I still think it is.

But his later work was not so great. His narrow and strict Christian morality started to show through.