The floor is open

Being able to cross the floor is fundamental to representative democracy

For as long as British Columbia has had political parties, politicians have occasionally switched affiliations while in office. Much to the chagrin of party operatives, one of the powers a Member of the Legislative Assembly has is the right to decide who they want to sit with in the House. This is known as “floor crossing”.

Floor crossing has been a major topic in Canada. Conservative Member of Parliament Chris d’Entremont crossed the floor to Mark Carney's Liberal Party, putting them within striking distance of a majority. If a federal election is called, he will have to face his voters who will decide if he made the right decision — or retire.

Political parties are a core part of Canadian democracy, but they do not technically exist within our parliamentary functions. The Premier is the elected official who can demonstrate the confidence of the house, which usually means being able to pass a vote with a majority of elected representatives — regardless of which party they were elected with. British Columbia has had minority governments, where the party in power does not have a majority and gets their votes from another party, as well as coalitions where parties formally agree to work together to pass legislation.

Even if a government has a majority of seats, if enough members of their party vote against them in a confidence motion — for example, the budget — the government falls and either another party is invited to try to pass legislation, or an election is called.

Parties themselves would likely prefer if elected officials did not have this ability. The federal NDP, which is constitutionally the same entity as their provincial branches, has previously introduced legislation to ban floor crossing. Canadians are almost evenly divided as to whether it should be allowed or not.

But without the ability for elected officials to leave or join a caucus, political parties would have significantly more power and influence than they do currently. If a politicians cannot break from their party, then the party has no reason to ensure they stick around, and the politician loses their leverage to ensure their constituents — the people who actually elect them — are represented beyond partisan lines. For some ridings, particularly in northern BC, crossing the floor is one of the few ways a back bench MLA can get everyone's attention.

The catalyst for change

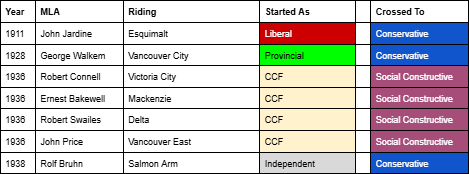

The first recorded floor crossing in British Columbia occurred less than a decade after the introduction of political parties in 1903. John Jardine first ran to represent Esquimalt in that election as a Liberal, narrowly losing to Conservative Edward Pooley by 27 votes. In 1907 he was victorious against Pooley, winning by 87. However, after being re-elected in 1909, he left the Liberal Party and joined the governing Conservative Party, led by Richard McBride.

While McBride’s party saw its support grow in 1912, voters were not impressed with Jardine’s decision. He ran as an Independent Conservative and placed fourth, losing the Esquimalt seat to Robert Pooley — Edward’s son.

In the lead-up to the 1924 election, a splinter group broke away from William John Bowser’s Conservative Party and formed the Provincial Party. Despite surging to 24% support province-wide, the upstart party only won 3 seats. The MLA for Richmond-Point Grey, George Alexander Walkem crossed the floor to the Conservatives, signaling the end of the Provincial Party and buoying Simon Fraser Tolmie’s rise to form government in the 1928 election. Walkem was re-elected as one of the six MLAs to represent the multi-member riding of Vancouver City.

In 1936 a group of disaffected members of the Canadian Commonwealth Federation, upset that the party had expelled their own leader, formed the Social Constructive Party. Robert Connell, who had become leader of the opposition in the 1933 election, had been at odds with the left wing of his party. Connell was a moderate, and had spoken out against a fellow CCF MLA who had given a speech on the merits of communism. After he publicly opposed a policy resolution within the CCF to support socialized banking and credit, his party threw him out.

However, three more CCF MLAs followed Connell. The party had only elected seven MLAs in the 1933 election, and with only three seats remaining, the four-member Social Constructive caucus formed the official opposition with Connell remaining at the helm. The CCF went into the 1937 election leaderless, and while they held their seat count at 7, the Conservatives made a comeback and became the new opposition. Connell’s Social Constructive Party ran 14 candidates but elected no one and quietly dissolved.

The stakes are raised

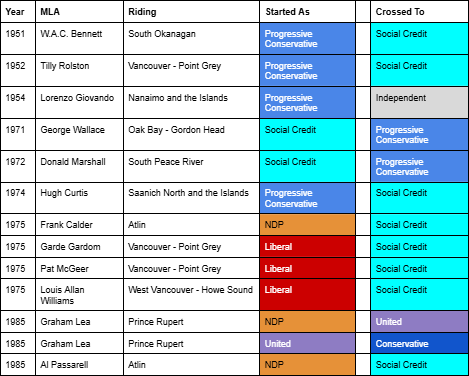

While most of the early floor crossers in British Columbia had minimal impact on the legislature overall, a disaffected Conservative switching parties in 1951 changed everything.

The province had been governed by a coalition party of Liberals and Conservatives, but the parties split in the lead up to the 1952 election. W.A.C. Bennett, who had sought the leadership of the Progressive Conservative Party and lost, split from his caucus to sit as an independent. As the election approached, he announced he was becoming a member of the newly founded Social Credit League.

Instead of returning to a back and forth between Conservative and Liberal governments, the voters elected enough Social Credit MLAs to form a minority. Their nominal leader during the election, Ernest Hansell, had not expected to win and had not even sought a seat for himself. As one of the only elected officials with governing experience, Bennett took the reins of the party and led them for the next 20 years.

W.A.C. Bennett was able to keep his caucus together for most of his tenure as Premier. However, in 1971 he lost the MLA for Oak Bay-Gordon Head, George Wallace, to the Progressive Conservatives. The party had only run a single candidate in 1969, but with a foothold in the Legislative Assembly they were able to mount a full campaign in 1971. Wallace’s crossing was harbinger of the times for Bennett, whose party went down in defeat in 1972, losing to Dave Barrett’s NDP. Wallace was re-elected and went on to lead the Progressive Conservatives, albeit with little electoral success, until 1977.

However, while Wallace’s floor crossing hurt the Social Credit Party, it was more floor crossings that brought them back. Hugh Curtis, the only other Progressive Conservative to be elected in 1972, abandoned Wallace shortly after and joined the Social Credit Party under W.A.C. Bennett’s son, Bill. He was soon joined by Frank Calder from the NDP, and three of the four members of the Liberal caucus. Having re-united the centre-right of the province, Bill Bennett led his party back into government in 1975.

Bennett was also able to largely hold his caucus together, with the exception of Graham Lea, who briefly joined an upstart United Party before defecting again to the Progressive Conservatives. That same year Al Passarell, who defeated former NDP MLA-turned-Social Credit Frank Calder by a single vote in the northern riding of Atlin, followed in Calder’s footsteps and left the NDP to join the Social Credit Party.

The great realignment

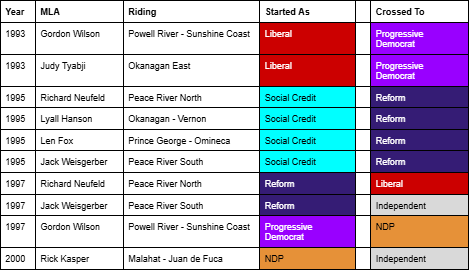

Social Credit ruled the province of British Columbia for 38 years total, but when voters decided they were done with them, they decided hard. In the 1991 election, the electorate ousted the Social Credit Party, now led by Rita Johnston, and elected the Liberal Party, led by Gordon Wilson, as official opposition. While the NDP were in government from 1991-2001, the centre-right of the province fought over which party would carry their banner.

Wilson, however, had been caught in an affair with fellow MLA Judy Tyabji, and was defeated in a subsequent leadership review. Despite leading his party from the wilderness to opposition, was quickly deposed from his position and replaced by former Vancouver mayor Gordon Campbell. Furious at his treatment, he and Tyabji both broke from their former party and formed the Progressive Democratic Alliance. Wilson was re-elected in 1996, but Tyabji was not.

At the same time this drama was unfolding, the remaining members of the Social Credit Party tried to revive their movement. They elected former MLA Grace McCarthy as leader, who sought election in the former Social Credit stronghold of Matsqui. She was defeated by the Liberal candidate, Mike de Jong.

Seeing the writing on the wall for their former party, four of the seven Social Credit MLAs left their party and joined the right-wing Reform BC under the leadership of Peace River South MLA Jack Weisgerber. Weisgerber and neighbouring MLA Richard Neufeld in Peace River North were re-elected in 1996 under the Reform banner, but no other candidates were. Social Credit was unable to field a full slate of candidates and was completely wiped out.

All three third party MLAs from the 1996 election then left their respective parties. Neufeld followed the trend of the province and joined the Liberals, while Weisgerber quit Reform to sit as an independent. Wilson abandoned his Progressive Democratic Alliance project and joined Glen Clark’s NDP in 1999, serving in four different cabinet roles before being defeated — along with most of the NDP — in 2001. Wilson remains the only MLA in British Columbia history to cross the floor to the NDP.

The dominance of the Liberals

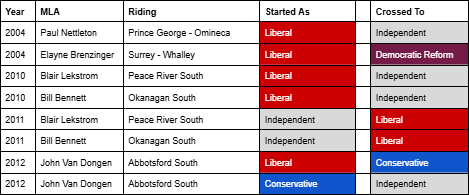

With the centre-right consolidated within the Liberal Party and the NDP losing steam, the newly-united “free enterprise coalition” swept the map and won 77 of British Columbia’s 79 seats in the 2001 election. With a supermajority under Gordon Campbell, the Liberal caucus was largely happy to stick with their party. Only two MLAs quit the government bench in Campbell’s first term — Paul Nettleton quit over opposition to Campbell’s plan to privatize BC Hydro, and Elayne Brenzinger over conflicts with Campbell himself. She then went on to help create the Democratic Reform party, but was subsequently defeated by the NDP’s Bruce Ralston in the 2005 election.

Then, in 2010, two MLAs quit the Liberal Party to protest Campbell's handling of the harmonized sales tax — something he promised not to implement and then did anyways. Both Blair Lekstrom and Bill Bennett — not the former Premier, a different MLA with the same same — quit the party. Already under pressure due to his catastrophic polling numbers, Campbell resigned. Lekstrom and Bennett rejoined the Liberal Party after Christy Clark became Premier.

Clark, however, seemed destined for the same fate as former Social Credit Premier Rita Johnston. With the NDP consistently out-polling the governing Liberals, Clark's viability as the centre-right’s standard bearer took a major hit when John van Dongen announced he was crossing the floor to the BC Conservatives under the leadership of former MP John Cummins. Van Dongen’s relationship with his new party quickly deteriorated, however, and shortly after crossing the floor he quit the Conservatives to sit as an independent. Suddenly the Conservatives no longer looked like a viable right wing alternative to the Liberals.

Premier Clark then recruited a criminologist named Darryl Plecas to run against Van Dongen, who won the Abbotsford South seat for the Liberal Party in 2013. Clark surprised everyone when she was reelected with a majority, defying the polls and her naysayers.

What goes up…

While Clark ultimately revived her party and won in 2013, the 2017 ended with the Liberals a single seat away from a majority. In the middle was the Green Party, suddenly holding the responsibility of choosing the next Premier of the province. They chose John Horgan's NDP, and signed a formal confidence and supply agreement.

The combined seats of the NDP and Greens narrowly crossed the threshold for a majority, but would likely require the Speaker of the House — normally a non-partisan position — to vote to break ties. While this functionally would work — it has happened a few times this last year alone — it was used as an argument by Clark that the Lieutenant Governor should call a new election.

All of Clark's potential avenues to hold on to her premiership came to a definitive end when Darryl Plecas announced he would seek the Speaker’s chair, which his party responded to by ousting him from their caucus. Plecas striking out as an independent was one of the first harbingers of the eventually collapse of the BC Liberal Party.

Horgan's government was stable, but dependent on the Greens. However, the Greens ended up in no shape to challenge Horgan's NDP when the party's leader, Andrew Weaver, abruptly crossed to the independent bench. While the party initially tried to say the split was amicable, stories emerged about drywall being put up between his office and the other two Greens, and it wasn't long before he was publicly criticizing his former colleagues.

When John Horgan pulled the plug on his own government in 2020, Weaver endorsed the NDP against his former party. The Greens were unable to hold his seat of Oak Bay-Gordon Head, and the Liberals were in no shape to take back the government. Horgan won a majority.

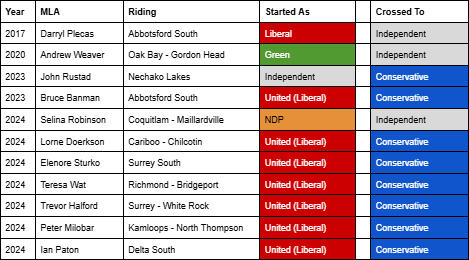

The Liberals never really found their footing again. After a disastrous rebrand and some poor by-election showings, the party's MLAs started looking for other pastures. First it was just expelled BC Liberal MLA John Rustad joining the Conservative Party. Then he was joined by Abbotsford South MLA Bruce Banman — a riding that somehow had three floor-crossing MLAs in a row. After three more MLAs crossed the floor to Rustad's Conservative Party, leader Kevin Falcon called it quits and withdrew all his candidates from the 2024 election.

Today’s changes

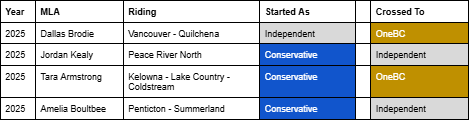

Rustad's coalition started to crack almost as quickly as it came together. Barely a few months after the 2024 election, Rustad faced his own floor crossing faction. Dallas Brodie, who he had kicked out of the Conservatives for her offensive comments on residential schools, joined with a fellow MLA who had quit in solidarity and formed a new far-right party focused on opposing reconciliation and LGBTQ rights.

For better or for worse, floor crossing has been one of the ways an individual MLA can have a huge influence over the legislature. Whether it's sitting as an independent to protest tax policy, or giving an extra-parliamentary party a voice in the legislature, elected officials have a lot of power in who they sit with once elected. Voters will sometimes punish floor crossers when they seek reelection — and sometimes they are happy to send them back as their representative.

Ultimately, Members of the Legislative Assembly answer to their constituents — not their party — and if they believe the best way to represent their community is to change affiliations, that is their parliamentary right.

Always a bit um floored by the Kabuki-like ritual theatrics around floor crossings. When someone leaves a party the party brass accuses them of all sorts of foul misdeeds and demands that the treacherous heathen step down and run in a byelection. When someone joins a party they are hailed as a conscientious patriot. Thanks for the explainer.

"Then he was joined by Abbotsford South MLA Bruce Banman — a riding that somehow had three floor-crossing MLAs in a row."

The only other place I can think of with that kind of record is Richmond-Arthabaska. André Bachand, André Bellavance and Alain Rayes all ended their careers as independents. Before April every one of their MPs had crossed the floor, and Eric Lefebvre's got a long career ahead of him.